Hello,

Thanks for your interest in learning more about embodied consent in medical care!

My name is Kyra Nabeta. I’m a former biochemist (MSc09, Queen’s University, Canada) who has worked for the past 12 years in marine search and rescue (Canadian Coast Guard) and as a volunteer medic (St. John’s Ambulance). Having more or less recovered from numerous injuries, I have significant experience as a patient in the Canadian medical system as well.

My poster is intentionally simple to make it accessible. The abstract is presented as it was accepted by the conference organizers, and I’ve written a brief paper to explain the concept in a bit more detail. All links will open in a new tab. The full text of the abstract and paper is below. I’m happy to chat more if you’re interested and to discuss any critical feedback you might have; please feel free to send me a message via the contact page.

Thanks again,

Kyra

A novel model of consent to promote embodied safety and trust between care providers and patients

Kyra K. Nabeta, MSc, CMNC

Paper to accompany poster #205 at the North American Conference on Integrated Care, 04-07 Oct 2021, Toronto, Canada

Conference theme: Meaningful partnership with patients, families and citizens

Pillar 5: Workforce capacity and capability

Accepted abstract

Introduction

High-quality people-centred care involves creating an environment in which patients feel seen, heard, and cared for. While these soft skills aren’t taught formally, they are integral to the patient experience and recovery process. Research into emotional health and embodiment is evolving and has attracted attention in the mental health field, but it remains obscure in Western medicine. Here, I propose a novel model of consent that encourages health care practitioners (HCPs) to recognize and clarify the power dynamics at play during treatment.

Aims, Objectives, Theory or Methods

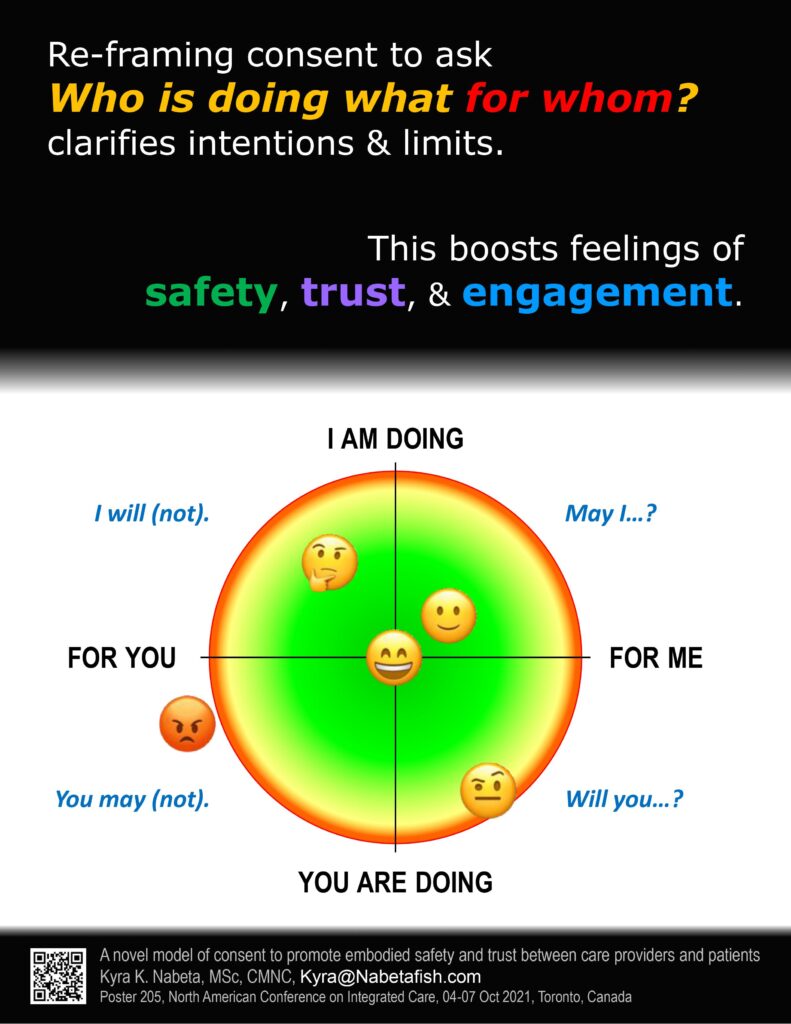

For a given an action, Dr. Betty Martin’s Wheel of Consent model asks FOR whom it is happening (rather than TO whom). The model identifies and explores the nuances of the different roles involved: giver vs. receiver; performer of the action vs. person on whom it is performed. By naming and discussing these roles at the outset of treatment, both the HCP and patient are empowered to notice, trust, value, and communicate what they feel as treatment progresses and to voice limits and boundaries, thus ensuring ongoing emotional safety and trust on both sides.

Highlights or Results or Key Findings

Dr. Martin’s model is widely acclaimed in trauma-informed sexological bodywork but has not yet been formally investigated in depth or adapted for the health care field due to the limits of embodiment research methods and to the stigma surrounding its current usage. Yet, the principles of frank discussion, plain language, regular check-ins, and openness to change are foundational for involving patients in their own care regimens, as they promote feelings of inclusion, engagement, safety, and trust in the care provider. As HCPs learn to initiate these discussions, they become role models to both patients and colleagues for voicing concerns at all levels of care.

Conclusions

By re-framing how consent is requested and ensuring that everyone involved is clear, at all times, about what is happening and why, both patients and practitioners can reduce instances of overstepping boundaries that leave patients feeling disempowered, helpless, and violated.

Implications for applicability, transferability, sustainability, and limitations

This training will have profound impacts on how HCPs view their personal and professional relationships, improving self-awareness, self-care practices, and, thus, resilience. This model is relatively easy to teach but requires a degree of openness on the part of the medical community to unconventional and counter-normative ways of relating.

Introduction

At some point in our lives, all of us have had things done to us that we were not asked about and/or did not agree to, to varying degrees. This shapes our relationships with our bodies and the world around us. On top of that, needing medical care is inherently vulnerable. Conscious and unconscious power dynamics (race, class, gender, ability, health status, etc.), coupled with the intimacy of exposing and discussing one’s anatomy and physiology, put healthcare providers (HCPs) in a position of power that must be respected. As a society, we are starting to recognize intergenerational mistrust[i] of the government and/or medical system and how it plays into patient behaviour on the personal and demographic level (Ibhawoh 2021).

Trauma-informed medical care is evolving as we collectively learn about the importance of the mental and emotional components of health. The concept is becoming established in critical care (Ashana et al. 2020), integrated care (Roche et al. 2020), medical training (Brown et al. 2020, TICC 2021), and first response (CCG 2019, FNHA n.d.).

The ideal patient experience involves feeling seen, heard, and cared for. Soft skills are integral to the patient experience and recovery process (Wong et al. 2017). However, soft skills are difficult to teach and learn because they are not quantifiable, they’re dynamic, and they’re unique to each relationship. The effects of touch, gaze, proximity, vocal control, and body language tend to fall secondary to efficiency, the use of personal protective equipment, and cost-benefit analysis. While research into emotional health and embodiment[ii] has attracted attention in the mental health field (Tantia 2019, Punkanen & Buckley 2020), it remains obscure in Western medicine.

Patients that feel emotionally safe with an HCP will trust them more and will, in turn, become more engaged in the recovery process. Here, I present a model of embodied consent[iii] that teaches people what consent feels like; this information enables people to set and protect their own boundaries and those of others. I propose that teaching embodied consent to HCPs will improve their ability to care for both themselves and others.

Highlights

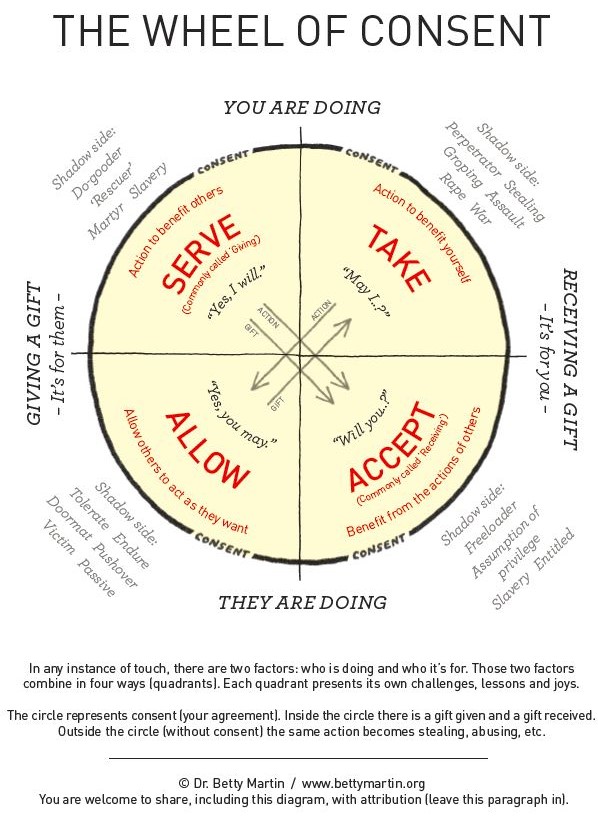

At its most basic, Dr. Betty Martin’s Wheel of Consent (WoC) model uses pleasant touch to teach people what YES and NO feel like. As participants explore different sections of the model, they learn what it feels like to give and to receive freely; to notice, trust, value, and communicate their desires, preferences, and limits; to recognize when they have not received clear communication; and to touch others with care and respect. They learn that they can choose what happens to them and that their choice matters (Martin & Dalzen 2021).

For a given an action, the WoC asks FOR whom something is happening rather than TO whom it is happening. The model identifies and explores the nuances of the different roles and relationships involved: giver vs. receiver; performer of the action vs. person on whom it is performed. Of note, it uncouples giving from doing.

There are two phases to the WoC.

- On one’s own, re-learning how to take in sensory pleasure.

- In pairs, learning the four different quadrants of the WoC by taking turns asking the following questions:

- How would you like to touch me?

- How would you like to be touched by me?

In the solo portion, participants examine their relationship to sensation and pleasure (direct and indirect). This involves uses their hands to slowly explore a small, inanimate object (e.g., small rock, fork, pen, etc.), focusing on pleasurable sensation. The person learns to tune into the sensation and engage the sensory and parasympathetic nervous system without being distracted by the dynamics of interpersonal interaction. This phase is required before anything in the second phase will work.

In the paired portion, each partner is assigned two roles:

- Giver or receiver

- Person who does the action or person to whom the action is being done

The two interpersonal dynamics the WoC explores are termed Serving/Accepting and Taking/Allowing (Fig. 1). To illustrate, I’ll describe a basic starting exercise that involves taking turns giving and receiving pleasant sensation in the hands up to the wrist for three minutes at a time.

In the Serving/Accepting dynamic, the Server is doing the action (feeling the hand) for the Accepter’s benefit (pleasure) without expecting anything in return. Both people are responsible for recognizing in themselves and voicing any requests, changes of mind, and limits. It might sound something like this:

Server: For the next three minutes, how would you like to have your hand touched by me?

Accepter: (pauses to consider what would feel very good, without guessing what the Server would be willing to do) Will you please massage the muscles at the base of my thumb?

Server: (pauses to consider if they are willing to do this) Yes, I will.

Server: (begins kneading the flesh on the Accepter’s hand between the thumb and forefinger) Like this?

Accepter: Almost. Can you please go a bit lower, over this way?

Server: (adjusts as requested) How’s this?

Accepter: Great, just like that. And a bit deeper pressure, please.

Fig. 1. The Wheel of Consent, as developed by Dr. Betty Martin (Martin & Dalzen 2021).

In the Taking/Allowing dynamic, the Taker is doing the action (feeling the hand) for the Taker’s own pleasure without looking for anything in return. It is the Allower’s responsibility to recognize and voice their limits. The conversation would sound similar to that above. The person in the Allowing role would ask, “How would you like to touch me?” and await the Taker’s answer. The Taker pauses to consider what they would like to do, then asks, “May I ___?” The Allower considers whether they are willing to have the requested action be done to them; if not, they may request modifications.

In both cases, the person asking the question is learning what it feels like to know what they want, to ask clearly for it, and to respect the limits of their partner. The person answering the question is learning how to feel the difference between what they are/are not willing to do/let be done, to trust that feeling, that they have a choice, and that they are responsible for communicating their limits. Communication eliminates the need to guess. Switching roles allows both participants to experience both sides.

There are specific protocols for language usage, relative body positioning, timing, troubleshooting, etc. (Martin & Dalzen 2021)[iv]. As participants get comfortable with working with hands, they can progress toward more complicated scenarios: more body parts, more time, fewer clothes, more people, different locations. Starting with just the hands provides time and space to notice the intricacies and nuance of the interaction.

The quality of a person’s touch improves when they understand viscerally that they have permission and will truly do no harm; they can relax and be present because they can trust that the other person will speak up to protect their limits. At the same time, there is an embodied sense of self-acceptance, connection, and fun that evolves, as one’s curiosity and desire are welcome alongside releasing the requirement to perform or achieve. There is a point during this training where the understanding clicks that is unique to each person and hard to describe.

The exercises described above are simple, but they are not easy. The focus of these exercises is on noticing the internal sensations that indicate different shades of yes or no and practicing talking about it. As participants progress, they will start to notice where else in their lives exist patterns and long-held habits of over-giving, expecting something in return, predicting the intentions of others, trying to control the reactions of others, performing, pushing boundaries, ceding limits, etc. Because touch allows a visceral experience, slowing down these interactions lets participants practice noticing internal change. Learning to trust, value, and communicate this information is the foundation for setting and respecting boundaries.

Conclusions

Consent is a dynamic and sliding scale, and the ability to establish limits is essential for fostering feelings of safety and trust. By re-framing how consent is requested and ensuring that everyone involved is clear, at all times, about what is happening and for whom, HCPs can reduce instances of boundary transgressions, thereby improving self-awareness, self-care practices, and resilience while reducing the risk of burnout and toxicity at home/work. HCPs doing their own work to figure out their patterns and tendencies when it comes to boundaries will have a domino effect because in medical settings, they’re the role models and the ones in the default position of power.

It’s important to note that the WoC doesn’t replace the current model of consent; rather, it adds a different flavour that makes it more nuanced and flexible and authentic. The key part is the addition of touch: the visceral experience adds an emotional element that can’t be denied. By learning about these foundational dynamics in a non-medical, non-emergency situation, the principles can be translated to different contexts later during professional training. To my knowledge, it has not been adapted for the more complicated scenarios that are often present in medical and emergency situations.[v]

The investment of time and money in this training is far less than what could be spent on care protocols that are not followed, requests for additional opinions due to a lack of trust, or treating evolving co-morbidities patient don’t feel able to share information out of fear or shame. We flip the question: instead of trying to get patients to engage, we can start asking what’s stopping them in the first place.

Why am I so passionate about this? Because it addressed a missing component in my work and home life: the visceral experience of feeling like my desires and boundaries matter. I’ve burned out at work (a few times), and I’ve had bad experiences with HCPs that left me feeling violated but powerless to do anything about it. How to fix this seemed an insurmountable problem till the WoC stripped it all down to boundaries: where do I feel like I can speak up, when do I not, what’s stopping me, why am I like this, and how did I learn these habits.

My hope is that, as these basic interpersonal skills become normalized, they will spread through role modeling of healthier interactions with friends, family, and lovers; with patients and colleagues; with careers and hobbies; with institutions and cultures.

References

Ashana, D.C., Lewis, C. & Hart, J.L. 2020. Dealing with “Difficult” Patients and Families: Making a Case for Trauma-informed Care in the Intensive Care Unit. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 17: 541–544. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201909-700IP

Brown, T., Berman, S., McDaniel, K. 2020. Trauma-Informed Medical Education (TIME): Advancing Curricular Content and Educational Context. Academic Medicine 96: 661–667. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003587

CCG (Canadian Coast Guard). 2019. Trauma Resilience Training. Victoria, Canada: CCG.

CMPA (Canadian Medical Protective Association). 2006. Consent: A Guide for Canadian Physicians, 4th Edition. Accessed at https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/en/advice-publications/handbooks/consent-a-guide-for-canadian-physicians on 30 Sep 2021; last updated April 2021. Ottawa, Canada: CMPA.

Ibhawoh, B. 2021. Medical Racism and the Black Experience: Confronting Intergenerational Traumas. Oral presentation at the Trauma-Informed Care Conference (“It Takes a Village”), 19 Sep 2021. Hamilton, Canada: McMaster University.

Martin, B. & Dalzen, R. (2021). The Art of Receiving and Giving: The Wheel of Consent. Eugene, USA: Luminare Press.

Punkanen, M. & Buckley, T. (2020). Embodied safety and bodily stabilization in the treatment of complex trauma. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 5: 100156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2020.100156

Roche, P., Shimmin, C., Hickes, S. et al. 2020. Valuing All Voices: refining a trauma-informed, intersectional and critical reflexive framework for patient engagement in health research using a qualitative descriptive approach. Research Involvement and Engagement 6: 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-020-00217-2

Tantia, J.F. (2019). Toward a somatically informed paradigm in embodied research. International Body Psychotherapy Journal 18: 134–145.

TICC (Trauma Informed Care Conference). 2021. McMaster’s 3rd Annual Trauma Informed Care Conference. Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: McMaster University.

Wong, E.L.Y., Lui, S., Cheung, A.W.L., Yam, C.H.K., Huang, N.F., Tam, W.W.S. and Yeoh, E. (2017). Views and experience on patient engagement in healthcare professionals and patients―how are they different? Open Journal of Nursing 7: 615–629. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2017.7604

[i] i.e., mistrust that is passed on from generation to generation through behaviours, attitudes, and culture.

[ii] Embodiment = the internal sensations associated with concepts like safety, trust, agreement, etc.

[iii] The concept of consent is complicated and evolving (CMPA 2006). My intent here is not to replace the current paradigm but to introduce embodied consent as an additional factor to consider.

[iv] See also https://bettymartin.org/videos/

[v] If you are interested in helping with this translation, please contact me!